The Role of the Digital Twin in National Security

Jane DOE (00:00): The following podcast was recorded in 2023. Thought leadership, titles, current events, legislation, and technology may have changed since it was originally recorded.

Dr. Michael Grieves (00:11): … to my simple battleship description, I mean, if you had the digital twins, of your adversarial capabilities, and could run models and simulations about where the weaknesses were, and what you would do in terms of being able to defeat them…that's a big, big deal. And again, having digital twins, of those sorts of things would be advantageous.

Jane DOE (00:34): The opinions and views expressed in the following podcast do not represent the views of NIU or any other US Government entity. They are solely the opinions and views of the speakers. Any mention of organizations, publications, or products not owned or operated by the US Government is not a statement of support and does not constitute US Government endorsement.

(Intelligence Jumpstart intro music)

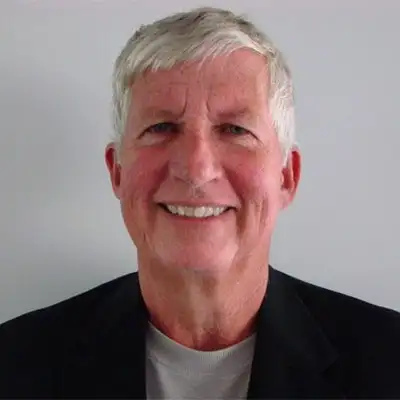

Jane DOE (00:57): Welcome back to the Intelligence Jumpstart podcast. I am your host Jane DOE. On this episode, I speak with the father of the Digital Twin, Dr. Michael Grieves. Dr. Grieves is an internationally renowned expert on Digital Twins, a concept that he originated. His focus is on product development, engineering, systems engineering and complex systems, manufacturing, especially additive manufacturing, and operational sustainment. Dr. Grieves has written seminal books on Product Lifecycle Management and the seminal papers and chapters on Digital Twins. He has consulted and/or done research at some of the top global organizations, including NASA, Boeing, Unilever, Newport News Shipbuilding, and General Motors.

In addition to his academic credentials, Dr. Grieves has over five decades of extensive executive and deep technical experience in both global and entrepreneurial technology and manufacturing companies. He has been a senior executive at both Fortune 1000 companies and entrepreneurial organizations during his career. He founded and took public a national systems integration company and subsequently served as its audit and compensation committee chair. Dr. Grieves has substantial board experience, including serving on the boards of public companies in the United States, China, and Japan.

Dr. Grieves earned his B.S. Computer Engineering from Michigan State University, an MBA from Oakland University, and his doctorate from Case Western Reserve University.

Jane DOE (2:17): Dr. Michael Grieves, thank you so much for joining me on the Intelligence Jumpstart podcast today. So, we're going to talk about the Digital Twin. And the term itself was coined by one of your colleagues, NASA's John Vickers, however, you're widely known as the father of the Digital twin. Did you just wake up one morning and have this conce pt in mind? Can you tell us a little bit about how the digital twin came to be?

Michael Grieves (2:43): Sure. So, I didn't…this was not a eureka moment. Luckily, I've been involved with computers since I was in high school, which was fairly unusual in the '60s, but I went to a National Science Foundation program, and learned to program, and then got into the computer industry when I was still in my teens. So, I've always been interested in the idea of computers, data, and information. And I've always started in the head in the back of my mind, the idea that we could reflect the physical world, in a virtual or digital one. And in point of fact, the first name I had for this model was the information mirroring model, which is not nearly as cool as Digital Twin. But it sort of reflected the idea that we absolutely could take the physical world and represent it in a digital. And a point of fact, humans have done that since time immemorial. We've had virtual worlds in our own minds, as we've thought about things and predicted what the future was going to be a model of simulation, within our own minds.

In fact, I've got a chapter going in, where I said, we've been doing simulations since prehistoric man figured out how to get a man with the runoff a cliff, so he could feed his fellow hunters. But I, in fact, started a computer company and, and got tired of dealing with the accountants and attorneys and went back and got my doctorate in the late ‘90s. And thought very much about, you know, how do we think about information. And there's a lot of…there's tons of definitions, but the one I kind of came about was the fact that information is a replacement for wasting resources, by taking any tasks that I'm thinking of it…and humans are basically, we're goal-oriented task solvers. Right? And so, I can take any task and divide it into two pieces. One is the most efficient use of physical resources that I could think of. So, whether it's designing a product, figuring out how to rescue hostages, and a hostage situation, or even getting three kids to do their after-practice routines,

I can divide that into two pieces, one is the most efficient use of resources, and everything above is wasted.

Where information comes in is that basically, I can replace not the physical resources, I need to do the task, but all the wasted stuff. And I'm saying ideally, but if I, if I kind of knew where I'm supposed to go, or a practice has been canceled, you know, I wouldn't basically drive those places. So, my fundamental understanding here, and the reason for digital twins, is that information is a replacement for wasted resources. And it comes about in all kinds of capabilities. And the two things that humans want to do is replication…what's going on in the real world and to have an understanding of what reality is…and then predicting what's going to happen.

So let me take a kind of simple example from a game that has IC implications. And that's the game of Battleship where two people sit there, and they plot their battleships on their little grid and, and they basically then call out coordinates to try to sink the opponent's battleship. And whoever sinks the most sinks them all wins. Right? Well, if you had a digital twin of their battleship thing, you'd win. You know, I mean, it’s basically it's call out all the numbers, and the game is over.

And that's sort of the idea that sort of information as a replacement. None of your battleships have been sunk. All of there's have been sunk and you've done it in the most efficient way possible. So that's kind of the whole premise behind the digital twin is to basically move work into the virtual world, where it is far, far cheaper in terms of moving bits around and moving around expensive atoms. And bits get cheaper every day, and atoms get more expensive every day. So that's the underlying premise of the digital twin and why I came up and said, you know, we have the physical objects in the physical world that we've always had and, we now have this ability to have a digital world and digital objects. And by the way, then we have a whole bunch of virtual spaces where we can do all kinds of different things, to look at the variations on a theme.

So that was the whole premise. You know, I released it the first time in 2002, I had no idea it was going to take off like this. And the good news is John Vickers came along and gave it a great name. So, I think that probably helped in its adoption.

Jane DOE (06:46): Your mention of Battleship takes me back. But, I'm new to the term digital twin. I heard about it from a colleague who used to be a senior research fellow in the Ann Caracristi Institute for Intelligence Research a t the National Intelligence University. Adrian Wolfberg, I'm not sure if you're…I think.

Michael Grieves (07:06): He was a fellow classmate of mine at Case Western. We're both graduates from the executive doctorate program.

Jane DOE (07:11): Cool, so you do know him? That's awesome. Yeah, small world.

I suspect that many of our listeners, as well as myself, don’t really know what a digital twin is… and it's very technical if you get into some of the research that you've published. And I'm hoping to frame our conversation moving forward for the non-technical person in our audience. I’d like to talk about some of the use cases that are, you know, specific to the Intelligence Community.

Michael Grieves (07:35): Yeah, so um, so my first comment is, really, they’re misnamed. It doesn't matter about having much intelligence. What you want is information. They should be the information community, because, again, information is a replacement for wasting resources. And having intelligence and no information doesn't do a lot of good.

So, there's, there's a number of different kinds of use cases that you could have. For example, digital twins have adversarial capabilities is extremely important. So, to my simple battleship description, I mean, if you had the digital twins, of your adversarial capabilities, and could run models and simulations about where the weaknesses were, and what you would do in terms of being able to defeat them…that's a big, big deal. And, and again, having digital twins, of, of those sorts of things would be advantageous.

We're seeing digital twins of assessing cybersecurity. I mean, the ability of having a digital twin, and the physical one running side by side…and when the physical one starts to do some strange things, with a digital twin is not doing…it's an indication that something has gone awry because what you think should be happening ought not to be happening in the physical world. So, in a point of fact, I basically say for those sorts of things, and for like autonomous vehicles, we ought to have digital twins of all those so we can have in essence overwatch capability of the physical things out there.

You know, if I put on sort of my hat about deviousness…honeypot digital twin…so being able to suck your adversaries into thinking that you have these sorts of capabilities and they're not actual. In fact, I've seen a couple of papers where they're proposing digital twins to basically suck your adversaries in. I mean, if you kind of look at, at, you know history, one of the…you know, information is a replacement for wasted resources.

But it also can be negative, and you can cause your adversaries to waste tremendous amounts of resources if you feed them the wrong information. So, I don't know if you're familiar with Operation Mincemeat in World War II…where we basically dressed up a dead body with papers to try to convince the Germans, which we did, that we were going to attack in, in Greece and not in, in Italy. And they bought into it and moved all their forces there and we went into Italy. I mean, that was a huge, huge use of information in the negative sense to cause your adversaries to do that.

You know, one that I've actually presented what was…and I mentioned it earlier…was mission support for hostage situation. The ability of going out and doing a reality capture of where you're gonna go…knowing where all the adversaries are…knowing exactly where the hostages are, and then being able to keep that up to date and a digital twin. I mean, you're talking about saving lives and I don't know that you can put a price on that kind of use of information.

But, but there's all these kinds of things where, in essence, the core issue is trading off information for wasted resources or using information. In this case, what I call negative information causes your adversaries to expand the huge amounts of resources, on something that doesn't mean anything. So, I think there's huge, huge opportunities there. Both to protect ourselves and also to take advantage.

Jane DOE (10:54): It's amazing what we can accomplish with this tool. In one of the symposiums you spoke at, you stressed the importance of having the digital twin at conception of the actual physical world. And I’d like you touch on the importance of that as well as what the digital twin lifecycle looks like from cradle to grave.

Michael Grieves (11:13): And that's a great question. Because…so I divided the… everybody's product lifecycle, I mean, including humans, into four phases, I mean, basically, you create the product, you manufacture or build the product, you support and operate the product, which is generally always the longest period of time, and then you dispose of the product. Okay? So that's sort of the issues.

You mentioned at the beginning, and I've gotten into this discussion numerous times, with everybody saying, well, you don't have a digital twin until something rolls off the assembly line. And I think that is a real misnomer, because as soon as I intend to create a product … that I'm going to make a physical one of I have a digital twin. Because a real value is being able, as I said before, to trade off, bits for atoms. And what I really would like to do is move as much work into the virtual world as I possibly can.

So, I would like to create my product virtually. I’d like to go test it out virtually. I mean, I'd like to take, for example, developing an airplane and take the missions, it's going to fly for the next 50 years, and run it through to see how it performs. I want to manufacture it virtually to make sure that I manufacture the most efficient way possible. And then I want to support it virtually. And, and so for example, there is there was one real example I ran across where an airplane was being developed. And this, this is using older technology and what they call a cave, which was a virtual reality cave. And when they went to try to hook it up to the carrier fuel system, it was a mismatch. And so because it was all virtual, they could basically change that design. If they had made that airplane and sent it out to basically be fueled on the carrier, it would have cost hundreds of thousands, if not millions of dollars, to either rejigger the refueling system or do something to that airplane. So you're talking about again, you know, my trade off of information for replaced for wasted resources. That's huge. And so, the more work I can do virtually to get it all right, make all my mistakes, virtually, virtual mistakes cost me nothing.

Physical mistakes can be very, very expensive, especially when we're talking about loss of human life. And so, what I call, the prototypical digital twin or the digital twin prototype, where I'm using that to create a product is a huge, huge return on investment in terms of being able to get a product that performs to where you think it's going to perform. That's a quality product. I don’t care who manufactured it. If it doesn't do what the user thinks it's gonna do, it isn’t a quality product in my estimation,

Jane DOE (13:44): Right. I mean, that makes sense. What is the relationship between the digital twin, AI, and the Metaverse? I mean, to me, they seem like very integrated in spots—maybe kind of the same thing…the Metaverse and digital twin. I'm sure there's a difference. So, can you walk us through those differences.

Michael Grieves (14:04): Yes, so in fact, I'm working on a chapter right now for a book I'm doing for Springer in terms of digital twins, simulation and the Metaverse. And what's sort of interesting and it's forced me to do is to kind of say, okay, what is this thing that we're talking about? In probably the easiest terms the Metaverse is sort of code for the digital virtual environments. Okay? And so I mean, if you track the Metaverse origin back, it goes back to Stephensen’s book Snow Crash, which was a really kind of strange book, let's say and, and the Metaverse was a specific thing that was sort of social and avatar based, you know, a basically, a Cyberpunk’s Second Life is what it was…great book, by the way…I highly recommend it.

But that's not kind of the Metaverse that we're gonna want. I mean, we're gonna want … that Metaverse you could take a motorcycle and run it into a virtual wall at 100 miles an hour and it just stopped. Okay? So it didn't represent our physical universe. If we're going to have a digital twin Metaverse, as I'm sort of describing, I, I've laid out sort of capabilities that it's going to need to have. First of all…and there won't be just one Metaverse, there'll be all kinds of Metaverses and they'll be driven by use cases of what you're trying to use it for.

The Metaverse will need to support both replication, you know what's happening in the real world with my product, and also prediction. But the big one is all the laws of the physical universe are going to be implemented and enforced in simulation. If not, I can't test products. Right? What I want to have is different digital twins in it. So I'm going to need interoperability, big problem, separable hold topic, a whole different discussion.

We will have the ability of having immersive participants like, like the Snow Crash Metaverse did, and they can have some meta capabilities. So, I argue that my definition of the Metaverse really makes more sense than the Metaverse that was there because it didn't follow all the laws of the universe. But we’ll also have the ability of having synchronous time, which that Metaverse did, and also asynchronous.

I'd like to basically predict into the future, my airplane running, you know, 50 years of simulations. And then finally, the big one here, and this also is probably the entire book is the cybersecurity piece. If the fortress’ ability of basically going out to a remote area and erecting a fortress with walls and guards and, things don't work for the for virtual. So how do we protect, you know, our Metaverse from bad actors? So it's going to basically occur because I think the next step here is we are going to have platforms where people are going to bring their different digital twins for testing and things like that. But right now, if you just say Metaverse, I think that we're really at the early edge where people can in essence, define it on their own. And somehow it makes sense. And some of it makes no sense.

(Manolis Minutes Music)

Manolis Priniotakis (16:55): I’m Manolis Priniotakis, NIU’s Vice President for Research & Engagement and this is this episode’s Manolis Minute.

Our next episode. Which is part of our series within season three on Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility topics, focuses on neurodiversity.

In 2023, a research team from the RAND Corporation, led by researcher, Courtney Weinbaum, conducted a study of the role neurodiversity in the national security workforce.

Based on interviews with national security and intelligence leaders and reviews of policies and documents, the study found that:

1) Neurodiversity can strengthen national security

2) Neurodivergent diagnoses are treated as a liability within the US Government

3) There is almost no data on the current size of the neurodivergent population in the US national security community … meaning it is a complete unknown.

4) As a result, officials appear to believe that there is almost no prevalence of neurodivergence in the national security workforce and that the lack of visibility is not due to any form of systematic discrimination or policy approaches.

5) They also found that several aspects of the USG recruitment and hiring process can be barriers to a neurodivergent workforce … to include unclear job descriptions, complex processes, interviews that focus more on social skills than technical knowledge, and lack of awareness of clearance processes.

6) Finally, once neurodivergent personnel are on board, it is challenging to navigate a workplace that was not designed with them in mind or able to easily make accommodations for their needs.

The authors also provide a number of recommendations, but I’ll leave those for you to find when you read the report.

The title of the report is Neurodiversity and National Security: How to Tackle National Security Challenges with a Wider Range of Cognitive Talents and is available on the RAND Corporation website: www.rand.org.

Thanks again for listening to Intelligence Jumpstart. For more information on NIU, please visit our website, www.ni-u.edu.

Jane DOE (19:13): It's pretty fascinating. Actually, we had a guest, who's referred to as the Godmother of the Metaverse in our first season, and she talked a lot about the Snow Crash and the Metaverse as, you know, we're experiencing it right now and our ability to actually deal with cybersecurity, which is a huge piece with all the technological advancements we’re seeing right now. But, what about our understanding of space? How might the digital twin technologies be used to advance that understanding? And do we get sufficient data from the Webb telescope or other data collections to create useful models?

Michael Grieves (19:50): So…and I have to say, for example, I think space may be easier than for example, our own climate…like I gave a talk at for NASA, NOAA, and I don't think there's any more complex system in our climate and we are nowhere near being able to predict what happens there. Space is a little bit different. I do think that we have a fairly good understanding of that kind of capability of what's out there. I mean, it's, you know, we do have some interesting models of space and astrophysics that make sense. Of course, if we find out that we're in a simulation, and space is not really space, all bets are off on that one. But let's assume that there is a reality here that space actually is a physical thing. And we're not, we're not just simulations in somebody else's simulation thing, which, by the way, is a theory.

But I think that that, you know, every time we do something, and like the Webb telescope was the latest, in fact, I got to see it firsthand when I was at NASA. We are getting better and better data about things and our predictions are pretty good. Again, what do we got, two things…replication…can we know what's going on? little tough to know what's going on lightyears. But we can sort of do the calculations on that, and then predicting and so, you know, you have to hand it to Einstein who predicted that, that the theory of relativity would bend lights…the stars from lights around a black hole, you know, 100 years ago.

So, I think we have a decent sense of that. And orbital mechanics is probably a lot easier than even, you know, negotiating a freeway in the Washington DC area. So, I'm pretty comfortable that we're in fairly good shape with respect to understanding. We get more and more of that every day. But, quite frankly, that doesn't really change things on earth. And I think I think our bigger problem is down here in terms of understanding what we can do and, you know, being able to predict outcomes in just one day in things like manufacturing products, for example.

Jane DOE (21:58): Right. Not to dwell on that, but do you think that they'll use a digital twin … and maybe they already … to create a metaverse Mars colony…or, you know, habitats that simulate life on Mars?

Michael Grieves (22:10): Yeah. So, I got the opportunity to meet Buzz when he was at Florida Tech. So, I mean, there's some really big thinkers here in terms of doing that. I would expect that if we're really getting serious about Mars, we will create a Metaverse of the Mars environment so that we can understand and run all the different simulations and problems between you know, getting from here to Mars and then being on Mars and building structures and handling all the necessities of life that we're going to need a tank to handle there.

One of the ironies I think, is that…if you remember the movie Martian, was that Matt Damon?

Jane DOE (22:55): Yeah, I think so.

Michael Grieves (22:55): Matt Damon or Ben Affleck, one of the one of the two. You know, how much money that movie made, we probably could have funded a Mars Metaverse.

Jane DOE (23:05): That is so true.

Michael Grieves (23:05): But I, but I think that we would be, we will, we will basically create a Metaverse where we can basically model and simulate all the things that they're going to run into up there and be able to deal with that. And again, they're gonna be a minimum 20 minutes away. So, we're going to need to have that kind of capability to understand what's going on.

Jane DOE (23:29): Wow. Very cool. Can we talk a little bit more about the digital twin’s capability in predictive analytics … to make those connections and to explore more data-driven relationships? Can you also provide examples of how this could be applied in law enforcement, the Intelligence Community, private sector, or academia?

Michael Grieves (23:50): Everybody wants to, in law enforcement, wants to hear me say, yes, Minority Report is going to be a reality. I don't see that happening. Okay?

I think we can model them seemingly everything in the universe except human behavior. So we may be able to do such things as predict an area of basically crime in terms of enmass, sort of the the molecular version of the fact I don't know what an individual molecule is going to do but I do know that we're gonna have this kind of capability. And be able to do that. In fact, I think that law enforcement has adopted crime stats and things like that…the ability of trying to predict is where their problems are so that they can marshal their forces to that.

But, I think in terms of being able to, use these sorts of things, on individuals isn't going to happen. And that's going to be a disappointment to some people. But I do think that we can process data there. Remember, there's two things that we kind of do in terms of simulation. One is, is basically kind of physics-based. I mean, you know, if I drop a rock from 20 feet, I'm pretty sure I can compute, you know when it's going to hit the ground.

But the other thing is, is collecting data. So the ability of collecting a whole bunch of data, and then using what's called Bayesian probabilities of, of what's happened in the past, I can get some fairly good predictions. And, and, and I, in fact, in a recent paper, I basically said, that’s how I think we're gonna go into the hybrid between, here's our physics-based causation and here's our correlation.

And, causation is really tough and complex systems. So I think the correlation piece of being able to say, here are…let’s take manufacturing. I have enough machines out there that when I had this sensor reading, this sensor reading, and this sensor reading…failed within this particular thing with these probabilities, say, two months at 80%. And, you know, four months at 95% I can get out in front of the curve and be able to do what's called predict predictive maintenance, and be able to say that. I mean, right now, with our, with the way we do periodic maintenance, we've we fix things, some things too early, and we fix some things too late. If I could do predictive, maybe I fix a few things too early, but I'm probably going to catch most of the things and not fix them too late.

So, so I think that there's opportunities in prediction, I mentioned, you know, law enforcement, a hostage situation, knowing exactly what they needed to do and running simulations, in terms of what's the best approach. And, again, it’s going to be tough to figure out what the individual on the other side is going to do——the hostage taker. But they would know where the hostages were, I mean, they look at they just rescue that that girl, in who was who is kidnapped in the campground.

No loss of life. I mean, they had, I'm sure all the data about where everything was and knew that, yeah, I'd be very surprised if they hadn't done an infrared checking and created sort of a digital twin of who was where to understand what they could do and what they couldn't do. So, I think there's, there's great opportunities, and using digital twins, for those kinds of capabilities.

And then in the Intelligence Community, the idea of having the most information about your adversaries, and what their capabilities are and how you could defeat them. I mean, the price on that I don't think you can even calculate.

Jane DOE (27:08): So I read something that said and I don't want to attribute this to the wrong source, so you know, take this with a grain of salt. But I read something that said, Putin claims that whoever controls AI, and these, technologies is going to rule the world. Do you see that happening?

Michael Grieves (27:23): Yeah. My interpretation of that is, is in fact, you know, when people ask me, how do you protect against AI ruling the world, I say, make sure it has a plug. You know. So ….

Jane DOE (27:35): That's pretty easy.

Michael Grieves (27:37): Just, you know, it needs power. My view of AI is that it is an enhancement to humans. It's not a replacement for humans. And in point of fact, you know, if you if you run some of the AI things, it lies to you. I mean, it has no shame about it. Because it really doesn't, doesn't, it isn't necessarily grounded in reality. I mean, we are grounded in reality, whether we like it or not.

And I don't see there being an AI to control I think there's going to be a whole bunch of those things. And so I don't necessarily know, it isn't like controlling, you know, the, the one nuclear weapon in the world. It's not going to be like that at all. So, so…and I know that there's some very smart people that are that are quite concerned with this. But I think that it really is a giant correlation engine for the most part. And I think that we as humans are smarter than that. In terms of at a minimum, you know, stop it.

And so, so I don't necessarily think that, that our big problem was going to be AI, you know, we're all going to be, you know, slaves to an AI system somewhere. I don't see that as, as any kind of probability, we're gonna have to watch it. I mean, if we're letting AI control, for example, all the autonomous vehicles out there, and that goes back to my premises, we better have a digital twin of that. So that humans can get in the loop at some point in time. But I think digital twins is kind of the offset of an AI system is being able to have a secondary system that we can kind of know what's going on.

Jane DOE (29:14): Gotcha. So, if you spend any time around the Intelligence Community, you hear that we are very, very risk averse. And we don't take to new technology very quickly, just because, you know, there's so much unknown. What do you think are and have been the challenges of adopting digital twin technologies? And can you think of any solutions to overcome those challenges to support the IC and, you know, academia’s adoption?

Michael Grieves (29:41): Yeah, I mean, I think the biggest issue is always cultural. I mean, and I talk about that all the time. Especially, and while I will absolutely say it's not a bifurcated meaning, older people don't get it and younger people do sort of thing. There is a tendency for…there's an age differentiation. And so in a lot of cases, there's a thing, what I call retirement-itis. You come to somebody senior with, hey, we should do this. And they're thinking, boy, I got five years to retirement, I don’t want to do this thing. And so, so you've got retirement-itis, that's fighting there.

The other thing is, that you have to be able to show that your models do predict the future. If you have…I mean, you know, it's amazing that we still watch weather reports. For the most part, they’re wrong. You know?

Jane DOE (30:30): It’s true.

Michael Grieves (30:30): And yet, we continue to say, oh, it's gonna rain tomorrow, it's not gonna rain tomorrow. And, and the opposite actually happens. But in this particular case, especially in terms of this community, we're going to have to show that the models do have predictive powers. At least probabilistically. Okay. And so, so we're going to have to build up kind of confidence levels, that says, you know, when I see these sorts of things, this was the outcome of what happened. And, and I can predict it 85, 80% I mean, whatever we're comfortable with, in terms of that.

And so…and I think the other thing is, that if you, you're wrong once and you punish people for it, guess what, they don't do this, they are risk averse. So I think I think we've got we've got to basically take into consideration, we're basically breaking new ground here. And, and we need to be trying some things. Now, you don't want to go attack another country, for example, because you predicted it. But on the other hand, I think there are there are areas where you can basically, you know, count your bets on different things, knowing that you've got some probabilities here.

But I think technology is coming, whether we want to or not, I mean, when we talk about AI, all we want, it's coming. I mean, my big concern is quantum computing. That comes, you know, for example, you know, all bets are off on cybersecurity in a lot of cases. And so…but we can't say, okay, there's a law against quantum computing. It ain't going to happen. It's not at all I mean, I think we got to basically figure out how we're going to deal with this. And we better jump into the pool and start paddling around to understand what our capabilities are. Because if we're not going to adopt them, other people are.

I, I gave a talk a couple years back at a Defense conference and talked about the fact that that, you know, there are autonomous capabilities, autonomous devices would have weapons, and I had a senior Department of Defense official said, well, we will never put weapons on autonomous vehicles. I don't care whether you're going to or not. I mean, your adversaries are. I mean, so we're going to need to figure this out. And so we're along for the ride in a lot of cases here with it with the technology trajectories. And so, we better figure out how we're going to take advantage of those.

But I think culture is going to be kind of number one, we need to hire the best people we can find, and throw them at this. Because if we've got kind of, you know, mediocre people, and our adversaries, got really smart people, we got a problem.

Jane DOE (32:58): Right. Absolutely. To your point about, quantum computing, it's coming whether or not we want it…Netflix just recently released a movie, it's called Heart of Stone. And it's about this secret, intelligence network with people from intelligence agencies across the globe, you know. They're the best of the best, they come together and solve the world's issues that, you know, nobody knows about. But they are using quantum computing. And, you know, it's like, the massive amount of, information they can access, they can break into any bank or government system…they can do all this and there's this guy from MI6, you know, he steals the heart, which the quantum computer is called, and he does nothing but evil with it. So, what are we going to do with this, and, you know, planning for it. How are we going to keep it safe?

To your point on culture, we had another guest say, culture eats strategy for lunch and it’s very true.

Michael Grieves (33:50): Absolutely. By the way, that was a good movie. Other than I didn't understand if the thing was packed with hydrogen, how it didn't blow up. But that's alright. That's another problem.

Jane DOE (33:57): Right. There's so many weird things in these movies.

Michael Grieves (34:02): You know, but remember, movies ar e kind of simulations. And that's what I think is interesting in terms of the overall simulation piece is, we've had simulations for a long time, they just happen to be movies. But now we have the community capability to run all kinds of variations of that to see what would happen. And I think that's where it gets fascinating.

Jane DOE (34:21): Yeah, definitely. Well, Dr. Grieves, thank you so much for your time today. This has been a really interesting conversation and I really learned a lot speaking to you about the digital twin. My last question is, if our listeners want to connect with you for your thought leadership, what is the best way to contact you?

Michael Grieves (34:39): They can contact me through my email address. That’s mgrieves@mwgdp.com. I have a YouTube channel out there with presentations. And if they're really interested in digging in on the puts you asleep papers, my Research Gate site has all my papers and chapters and things like that.

Jane DOE (34:58): Excellent. Well, thank you again. I appreciate your time, and I look forward to sharing our conversation with our listeners.

Michael Grieves (35:04): It was fun. Thank you. Great questions.

Creators and Guests